PROFIT-SHARING FOR EQUALITY—TWO CASES OF FAIR TRADE INNOVATION

Meet Sidamma. She’s part of a business that redistributes profits from the top down, uplifting individuals out of poverty. In this blog post, you’re going to meet Sidamma and others like her who are leading innovative Fair Trade Enterprises into a more equal and fair future with a profit-sharing model.

First, let’s take a look at the problem that inspired these individuals to run their businesses differently.

Today, the markets where we produce, buy, and sell things are dominated by profit-driven businesses. These businesses don’t just put profit above other considerations – they concentrate that profit among an elite few at the top, assuring us that they must do so to further innovate and create more jobs for regular people.

But there’s a problem with this model. Despite its lofty promises, it’s failed to reduce social and economic inequalities throughout much of the world. According to Oxfam, in 2018, 26 people owned the same as the 3.8 billion who make up the poorest half of humanity and who saw their wealth declined by 11 percent. This statistic illustrates how wealthy business leaders have primarily used their profits to gain more profit, exploiting both the environment and human labour in the process. Clearly, there are issues with the status quo.

This is where WFTO Fair Trade Enterprises come in. These socially-driven businesses are challenging the conventional model characterized by profit maximization and wealth concentration, structuring their businesses so that profit – and power – is distributed from the bottom up.

Creative Handicrafts

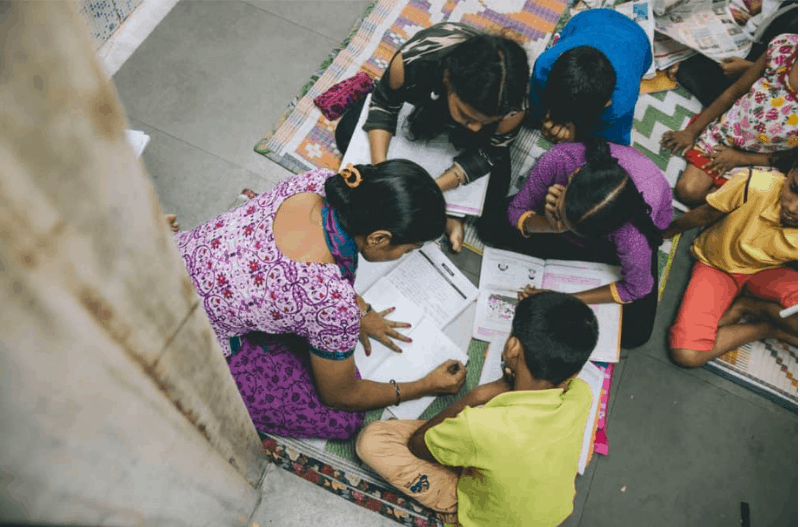

Take Creative Handicrafts (CH), a social enterprise producing quality apparel in India. Since its beginnings in 1984, CH has centred its mission on the social and economic empowerment of women artisans. They make up twelve cooperative groups of skilled and talented women, (over 270 people) form the company’s backbone. In a true illustration of “empowerment,” these artisans are all effective co-owners and decision-makers within the company.

Sidamma was one of the first women to join the organisation. Growing with the organisation, she was elected onto the board and has played an important role in identifying many disadvantaged women and showing them into Creative Handicrafts so they too can become independent.

There are two significant features of CH’s model. Firstly, the structure of power dynamics within the organisation. Employees hold positions on the company’s board, where they can voice concerns and discuss methods of improvement, from both a business and social perspective. Employees are directly involved in decisions that impact them, and their involvement has led to the establishment of programs in education, health, and capacity building. CH has developed programs with women’s empowerment, gender equality, and ending violence against women, as its guiding stars.

When Sidamma came to the organisation she was an emigrant who could not speak the local language, she also faced various atrocities at the hands of her husband as she was unable to bear him a son. At Creative Handicrafts she found support and companionship. She says for her it was about more than being economically independent but also having someone to care for her.

Secondly a vital feature of CH is their profit sharing model. In addition to receiving a monthly living wage, at the end of the year the profits made by each cooperative group is shared among the employees. This bonus income may amount to 2-4 times what an employee would normally earn each month. Lalita Pawar, President of CH, speaks strongly on the organization’s core value of equality: “It is because of this principle, that I, being a beneficiary, could one day become the Chairperson of the board of trustees of this organization.” She adds: “It is my desire for the years ahead that this principle of equality shall not change and shall remain etched in stone, not just for those associated with us, but in the society and world that we live in; that we may always remain inclusive, maintain equity, be open to new ideas and people, and finally keep the poor and marginalized close to our heart.”

The profit sharing model isn’t just about distributing money. It’s about giving workers the agency to make real decisions about the business’s direction.

CORR-The Jute Works

A similar innovative model of bottom-up management is illustrated by CORR – The Jute Works, a women’s non-profit handicraft marketing trust and exporter of quality handicrafts. Based in Dhaka, Bangladesh, The Jute Works represents more than 5,000 rural women artisans and empowers women through handicrafts production. Aligned with a mission that puts these artisans at the heart of their business, The Jute Works is structured to give artisans majority control of the board. Five out of nine positions are elected from the women cooperative groups by the artisans themselves. Through shared ownership and decision-making power, artisans take control and present their own interests. They make decisions regarding profiting sharing and reinvest profits into programs that provide access to credits, business training, health and nutrition, children’s education, and women’s rights training – all essential to creating sustained change and reducing income inequality.

An outstanding feature of both of these organizations is the employment and direct involvement of women in all their operations and decision-making. In fact, you can’t talk about innovations that promote equality without talking about gender equality. To draw on a common saying: when you give a man a fair wage, you improve his life. When you give a woman a fair wage, you improve the life of a whole family. By distributing profits fairly.

Author: Cherry Sripan

Images : (1-3) by Creative Handicrafts; (4) by CORR- The JuteWorks